Brainstorming the challenges in African PPPs

January 03, 2019

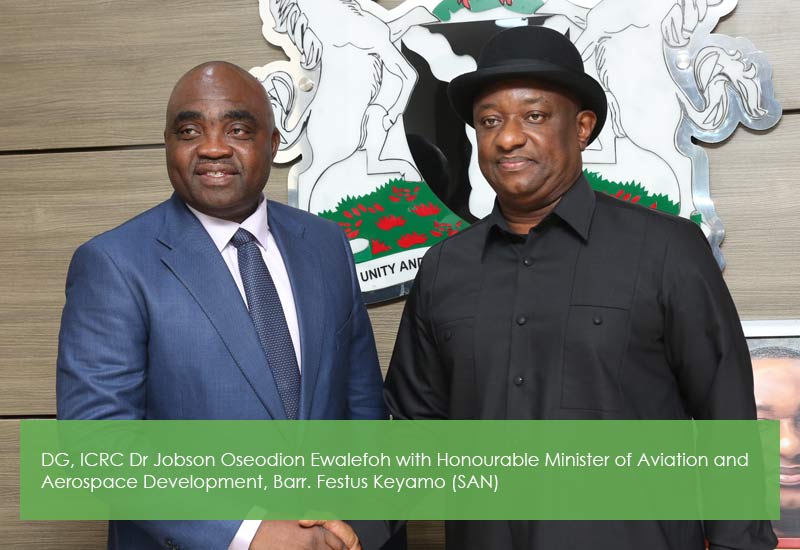

On 16 October 2018 in Abuja, the Nigerian Infrastructure Concession Regulatory Commission (ICRC) and the Global Infrastructure Hub (GI Hub) played host to nearly 100 government representatives from 9 different countries – including about 70 delegates from 30 Nigerian ministries, states and parastatal agencies – to discuss risk allocation in Public Private Partnerships (PPPs).

Proceedings were opened by insightful speeches from Vice President Yemi Osinbajo SAN, and the Director-General of the ICRC, Engr. Chidi Izuwah, both focusing on the importance of well-designed PPP models in helping to accelerate infrastructure developments in Nigeria. International law firm Norton Rose Fulbright and leading Nigerian law firm Olaniwun Ajayi then led proceedings for the rest of the day, delivering a series of lectures, workshops and negotiation exercises, with the aim of highlighting some key challenges in PPP project structures and how these could be approached by both private and public sector bodies.

It is clear that successful PPP deals are thin on the ground in Africa – it has been said that only 8% of initiated projects reach financial close – and even among those there have been some high profile failures, such as the Rift Valley Railway project in Kenya. One of the more engaging sessions during the day was a workshop asking each agency to put forward their key challenges and solutions for delivering PPPs. This gave rise to a lively debate and a number of useful observations by the attendees, showing the benefit of having a regional workshop.

Reduction of corruption

Corruption was universally acknowledged to be major problem holding back the procurement of major projects, but given the broad and endemic nature of the issue across society as a whole, there was no clear way forward to address this. Narrower solutions would need to be found to address specific issues in a PPP context, such as ensuring that there is greater transparency in bidding processes and grievance mechanisms for dissatisfied parties.

Steady political support

Closely linked to this were political considerations. Steady and firm political support for PPP projects is essential, but the development cycle for PPP projects is usually quite long – with 4 years or longer from project inception to first drawdown of funds being common – and political support may waver when politicians can see elections coming, against the fear that the next administration will be able to cut the tape on the new project and take political credit.

Having a long-term infrastructure plan

One solution that was offered to this was to have a clear, public long-term infrastructure plan that remained stable from administration to administration, which would allow incoming officials to choose from a menu of suitable projects to promote, and for outgoing politicians to be given credit for projects that were pushed forward in their term but delivered subsequently.

Other attendees also stressed the value that a project pipeline could bring, noting that IPPs and other energy projects were typically developed before other infrastructure sectors, and that this has helped build up investor confidence in the jurisdiction.

Dealing with political “input”

Most of the attendees acknowledged, regretfully, the flip-side of political support: political interference, although the euphemism “political input” appeared to be the less-provocative term employed by some attendees. It was noted that all projects had their own political hurdles along their way.

Another common problem was the “PO Box 1 issue”; namely, projects being pushed directly to the President for support or resolution, sometimes resulting in a political push to deliver projects that have not shown a bankable business case.

The need for adequate project preparation

Pushing forward projects without adequate preparation dramatically reduces the chance of the project being successful. The ICRC Director-General noted that a lack of human capital was part of the problem, and that funding and engaging suitable transaction advisers early in the process was recommended, and where this does not happen international development banks could also be used to impress upon the government the importance of project preparation in developing successful projects. Poorly structured projects may also find themselves cut off from the mechanisms they need to ensure project delivery, as has been seen where political risk insurers have decided not to provide coverage to projects where they see an unsustainable risk allocation.

One agency noted that they had systematically looked at best practice across other African countries to ensure they were comfortable that the outcome of the project preparation process would give a satisfactory result.

Dealing with unsolicited proposals

A number of attendees noted that agencies could be inundated with unsolicited proposals, but lacked in guidance on whether to accept them, or how to deal with them. The same scrutiny and preparation that goes into a tendered project process should go into dealing with an unsolicited proposal. Some countries, such as Nigeria, have a very detailed procedure dealing with unsolicited proposals, which takes on board international guidance, but even where such procedures formally exist, political pressure can cause important safeguarding steps to be cut.

Improving understanding of PPP

Attendees agreed on the need to improve public understanding of how PPPs work (such as their role in helping to fund public services and sensitising citizens’ willingness to pay), but there was also a call for a greater level of capacity building at government level, with attendees seeing a greater level of scrutiny coming from parliamentary members in particular. In addition, there was a feeling that the local private sector market needed to be educated in the same way, as otherwise there was a perception that PPP was just for foreign investors, contractors and advisers.

Ongoing review of signed projects

The South African delegation stressed the importance of ongoing review of signed PPPs, noting that they would review all PPP contracts on a 5-yearly basis so as to be able to keep the politicians properly informed. Recent studies by the GI Hub have shown the importance of active management of signed contracts by government bodies, noting that over 25% of signed PPP projects end up being extra-contractually renegotiated within the first 5 years. Circumstances change, and contracts cannot always predict and deal with such changes; the GI Hub’s research shows it makes sense for government agencies to remain adequately skilled and prepared to renegotiate their positions if that is in their best interests.

Other solutions – the NSIA approach

Against the backdrop of these challenges, it may be instructive to look at the approach being taken by the Nigerian Sovereign Investment Authority (NSIA), who have been granted a significant level of independence and stability to support and develop a infrastructure projects in Nigeria. NSIA is creating new opportunities to fund and support projects, through vehicles like the Presidential Infrastructure Development Fund (which will allow state governments to take an economic interest in the project companies developed by NSIA) and InfraCredit (to provide credit support to investors and banks on infrastructure transactions, in association with the multinational guarantee provider GuarantCo). In addition, NSIA is also looking at a range of innovative PPP models. These include smaller sized projects, setting up linked projects which have a cross-subsidy element, and adopting risk-structuring approaches to share some “traditional” PPP risks (such as demand risk) with the government party. The relative independence of the NSIA has allowed projects to be pushed forward despite political changes, and there have been some early successes, such as a $10m healthcare equipment project at the Lagos University Teaching Hospital and reforestation and land restoration projects in Ogun State.

Source: https://www.insideafricalaw.com/blog/2019/q1/brainstorming-the-challenges-in-african-ppps/